This post was originally published on spotlight.africa. It was in response to a viral video of a matric student’s final art project that contained imagery of demons and incorporated the Bible in a papier-mâché artwork. The video was taken, without permission, by a Pastor/Parent at the school who bemoaned that the School had abandoned their ‘Christian ethos’ and allowed satanic art. Days after the video went viral, finally the explanatory notes that accompanied the original artwork were made public – which, I think if anyone read them (you can read them here), and I hope more people do, I think they would agree with me that the charge of Satanism is unfounded. In this article I tackle the specific question of the use of pages from Scripture in art.

The controversial artwork - distasteful or an uncomfortable introspection?

South African social media was awash this week with speculation about a final art project by a Richard’s Bay matriculant, Gary G. Louw. Charges of ‘satanism’ abounded and there was a rush, it seemed, to crucify the learner and his school. Matthew Charlesworth SJ examines whether this charge is substantiated and whether, in fact, the artwork has more to say to Christians than perhaps they are willing to hear.

To be honest, I had never heard of Grantleigh School before. And yet this week it seemed to dominate so much conversation and debate in Christian circles because of a final year artwork exhibition. The exhibition explicitly prohibited photographs to be taken, and the artwork was in a sheltered and restricted display area precisely because of the controversial nature of the artwork. Neither of these stopped a parent who recorded and published it anyway, thus propelling this exhibition, and the parent’s concerns and worries, onto the phones and tablets of people all across the nation and far beyond its intended audience.

Let’s remember that the artworks were exhibited for the purpose of examination, as are other art works all around the country by students at this time of year. Sadly, this parent’s actions also took the art work out of context, and have kept Christian keyboard warriors very busy. The artist’s explanatory notes for the exhibition have since been published online, and are worth reading. In the ensuing drama, the artist has also been compelled to release the following statement:

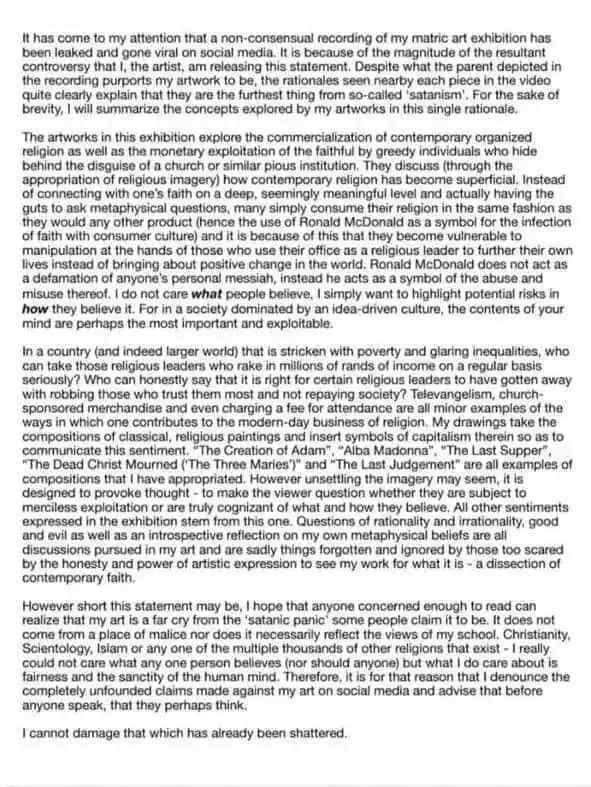

It has come to my attention that a non-consensual recording of my matric art exhibition has been leaked and gone viral on social media. It is because of the magnitude of the resultant controversy that I, the artist, am releasing this statement. Despite what the parent depicted in the recording purports my artwork to be, the rationales seen nearby each piece in the video quite clearly explain that they are the furthest thing from so-called ‘satanism’. For the sake of brevity, I will summarize the concepts explored by my artworks in this single rationale.

The artworks in this exhibition explore the commercialization of contemporary organized religion as well as the monetary exploitation of the faithful by greedy individuals who hide behind the disguise of a church or similar pious institution. They discuss (through the appropriation of religious imagery) how contemporary religion has become superficial. Instead of connecting with one’s faith on a deep, seemingly meaningful level and actually having the guts to ask metaphysical questions, many simply consume their religion in the same fashion as they would any other product (hence the use of Ronald McDonald as a symbol for the infection of faith with consumer culture) and it is because of this that they become vulnerable to manipulation at the hands of those who use their office as a religious leader to further their own lives instead of bringing about positive change in the world. Ronald McDonald does not act as a defamation of anyone’s personal messiah, instead he acts as a symbol of the abuse and misuse thereof. I do not care what people believe, I simply want to highlight potential risks in how they believe it. For in a society dominated by an idea-driven culture, the contents of your mind are perhaps the most important and exploitable.

In a country (and indeed larger world) that is stricken with poverty and glaring inequalities, who can take those religious leaders who rake in millions of rands of income on a regular basis seriously? Who can honestly say that it is right for certain religious leaders to have gotten away with robbing those who trust them most and not repaying society? Televangelism, church-sponsored merchandise and even charging a fee for attendance are all minor examples of the ways in which one contributes to the modern-day business of religion. My drawings take the compositions of classical, religious paintings and insert symbols of capitalism therein so as to communicate this sentiment. “The Creation of Adam”, “Alba Madonna”, “The Last Supper”, “The Dead Christ Mourned (The Three Maries”)" and “The Last Judgement” are all examples of compositions that I have appropriated. However unsettling the imagery may seem, it is designed to provoke thought - to make the viewer question whether they are subject to merciless exploitation or are truly cognizant of what and how they believe. All other sentiments expressed in the exhibition stem from this one. Questions of rationality and irrationality, good and evil as well as an introspective reflection on my own metaphysical beliefs are all discussions pursued in my art and are sadly things forgotten and ignored by those too scared by the honesty and power of artistic expression to see my work for what it is - a dissection of contemporary faith.

However short this statement may be, I hope that anyone concerned enough to read can realize that my art is a far cry from the ‘satanic panic’ some peopie claim it to be. It does not come from a place of malice nor does it necessarily reflect the views of my school, Christianity, Scientology, Islam or any one of the multiple thousands of other religions that exist - I really could not care what any one person believes (nor should anyone) but what I do care about is fairness and the sanctity of the human mind. Therefore, it is for that reason that I denounce the completely unfounded claims made against my art on social media and advise that before anyone speak, that they perhaps think.

I cannot damage that which has already been shattered.

The artist makes the point that his concern is not with what one believes, but how we believe it. In other words, the authenticity and actions of believers. I think that’s a fair point.

Freedom of expression and religion is for all

I think this incident has raised several issues we can reflect upon. We might immediately reflect on the role of social media in this story. The parent who broadcast his video, despite no permission being given to do so, exercised his right of freedom of expression – which is the same right the artist uses to defend his art. I think more people have been affected by the artwork than would ever have been had the video not been made. Given the parent’s objection, isn’t that a bit of an own goal?

There are other questions: Is it right to attack the artist through social media without engaging directly with him? Let us not forget that he is a young learner who is probably trying very hard to remain focused on his exams – how might these online and offline actions affect him? All of these are questions worth considering, but there are deeper ones too.

There is also the tension between the competing freedoms of speech and expression with the rights of believers to freedom of religion. We live in a constitutional democracy — and many other commentators have already explained the advantages of such freedoms — and how they ultimately allow for freedom of religion. This is a freedom which protects religious believers, and those who choose not to believe. If we attack it, do we not end up destroying our freedom to believe? We also cannot demand that our religion be respected. In fact, the reason the artist is critiquing religion is because he feels that Christians themselves do not respect its teachings, as evidenced by their hypocrisy and greed.

Fundamentally, I think that a religion must be freely chosen, and consequently everyone is entitled to question one’s religion, and to express their questions as they would like. This learner, who has already experienced censorship around his art and beliefs, created a response that reflected his criticism of religion and led him to adopt atheism. I would point out that it’s not uncommon for young people to fall out of faith… or to express such views in a triumphant, dramatic or provocative way. In this case, he has done so thoughtfully, however, and taken the risk to share his experience publicly – though he intended it for his peers and teachers, not the nation. Does this warrant the attacks he has endured, and specifically the charge of ‘satanism’?

What about the duty to defend the faith?

I would like to consider this matter from the point of view of a Christian, and leave the constitutional arguments to others. I’ve had people this week ask me why the Church does not complain; after all, they say, “if they criticized another world religion, would not, and should not, the response be more militant?”

On the framing of this as ‘us vs them’: My initial thinking is that Christianity is used in the artwork because the artist was, at least at some point, Christian himself, and his context is a school with a Christian ethos. He is not commenting from the outside, but perhaps like a prophet, is commenting from his experience from the inside, and describing how he felt, in conscience, bound to reject what he knows to be as inauthentic.

As a Christian, I also reject a prosperity cult distortion — some might say heresy — of the Gospel. I do not think that this necessarily leads one into atheism. There are authentic Christian beliefs and ways of living that avoid such a heresy, but I would grant that if he has not been able to see or experience such beliefs, then perhaps rejection is the logical consequence. But I would rather channel my energies into finding out why authentic Christianity is not reaching him, rather than blaming him for rejecting what any authentic Christian should reject too.

The second and perhaps more common objection is why we are not militant like ‘other religions’. I believe that is because it is precisely the point of Christianity. Most Christians would argue that we are not like other religions. Many would claim that we are called to love our enemies. This is not a retreat into ‘tolerance’. It is a command of the Gospel. We love our enemies in a way that seeks and prays for their good, not their downfall. We should seek to engage and understand what our perceived enemies are saying.

That’s precisely why Christianity is different, why Christianity is so much harder, and why it is that non-Christians find it so hard to see Christianity in Christians when we react just like everyone else. If we want to be a beacon to the world — to evangelize — we must always react first with love. And we must do this most especially when we are insulted. Is that not what we read in Mt 5:11 and Lk 6:22? Jesus tells us that we are blessed when we are persecuted for his name’s sake, but not if we behave like the persecutors in return.

An opportunity for dialogue

I’m reminded of what St Ignatius wrote in his Spiritual Exercises:

Let it be presupposed that every good Christian is to be more ready to save his neighbor’s proposition than to condemn it. If he cannot save it, let him inquire how he means it; and if he means it badly, let him correct him with charity. If that is not enough, let him seek all the suitable means to bring him to mean it well, and save himself.” St Ignatius, Spiritual Exercises, #22.

After reading the artist’s explanations of his artwork and so, in the greater context, it would have been better for Christians to have, in a spirit of charity, inquired of him what he meant and to endeavor to understand the meaning behind the artwork. I believe it would be better to take the substantive charges of consumerism, simony, greed, exploitation, hypocrisy and falsehood etc. that he raises in his artwork and to try and engage with the artist or artwork on that level first.

Only then can one engage on whether there might have been more appropriate ways to depict the artwork. A conversation conducted on that level would have a far greater chance of growing into dialogue, and would probably reduce the risk of otherwise good Christians appearing unkind and uncharitable. It might even engage a thoughtful person to see a side of Christianity which is not unintelligent or afraid of critique.

Christians should also remind themselves that art has always played a role in the life of the Church – dramatized perhaps ultimately in the symbolism of the liturgy. But with poor liturgy, and even worse homilies to explain the liturgy and its symbols and meanings, is it any wonder that Christianity is losing its ability to reflect on the deeper questions of life in art?

Let’s recall some examples of artistic and creative engagement when in 2018 the Vatican held an exhibition at the Metropolitan Gala in New York, and Cardinal Ravassi, the head of the Pontifical Council for Culture, has on several occasions engaged with artists in Milan and other venues of high culture. If we criticize and condemn other artists who are engaging with religion – I think we lose a vital opportunity to encounter and encourage and discuss the faith. Our God is large enough not to be harmed by anything certain people claim to be offensive.

We should rather use opportunities like this to engage in the substantive meaning behind the artwork. In this case – the artist’s commentaries on the prosperity cults, the dialectic between faith and reason, and the role of capitalism – all quite germane to our Church at the moment, especially with the Amazon Synod, which points towards the need for a greater attention to science, a greater caution against capitalism, and a more attentive relationship to the earth — requiring a moderation of our greed and ambition — and a proper identification by the Church, and especially her leaders, with the poor and the marginalized, not with the rich and the powerful.

Is defacing the Bible offensive?

Many have complained about the presence of demons in his art, yet throughout history there is a precedent for depicting demons in Christian art, along with angels, to represent good and evil. Instead I’d like to address the perhaps (for many uncomfortable) question about the artist’s use of torn pages from a Bible in his artwork.

“A Spectrum of Belief” by Gary G. Louw // Source

I grant that the use of torn pages from a Bible may seem sacrilegious, and this is the basis for many of the charges of ‘satanism’ against the learner by those on social media this week. But I think that is a bridge too far.

Certainly we believe that Scripture is the Word of God. We venerate Scripture at Mass in the liturgy and we ask Christians to read it and pray with it (and I would have a problem of tearing Scripture in the context of the liturgy), but Scripture appears itself in artwork and icons, represented in the form of a page or book. We know that this representation of Scripture is not itself Sacred Scripture, but points to the Word of God. So I would like to make the following points.

The first is whether this is an offence against Scripture? I would grant that for fundamentalist Christians, this could be offensive. Part of the reason for this is they often adopt a rigidly literal understanding of the text of the Bible, unlike other Christians who acknowledge the consequences of translation, editing, and interpretation, and so they can sometimes approach a form of bibolatry in their understanding. But let me tell you why I am not offended.

Firstly, I do not believe in magic, and so when we venerate the Word at Mass, we are not venerating the specific paper, printing, binding and composition of that specific Bible, as if it was a consecrated host which we believe to be God-really-present to us there and then. Rather, we are venerating Sacred Scripture in general, to which we all have access and through which we can all pray to God. Whether the Word of God is contained in a book, an iPad, or an audio recording… it is the words, not the medium, that is the message.

Whether the Word of God is contained in a book, an iPad, or an audio recording… it is the words, not the medium, that is the message.

Secondly, I am not denying that the Word of God is sacred. But the pages of a particular book are pages of a book. The power of Scripture is that the Word changes the hearts of believers. I do not believe the Word of God has been destroyed or damaged by this artwork, especially when one considers the intent of the artist (which the video that went viral deliberately ignored).

In an art-form where the choice of material is significant, the artist chose to use pages from the Bible to paper over his face to represent the ‘religiosity’ of himself as a believer, and to also show how whilst one was meant to be ‘holy’, there was hypocrisy that was visible – in himself and his fellow believers. This was represented by the ‘horns’. The use of Scripture in the artwork was intended, then, to reflect the religiosity of the believer. Is that a perverse or insulting understanding of belief or believers? The more religious figure would be more acquainted with the Bible, and so is represented by more of it in the papier-mâché<.

Is he wrong to tear the pages – could he not have written biblical passages on a plain papier-mâché? I certainly think it’s controversial – but isn’t that the point of art, to make one re-assess and think? Personally, I do not find his intent to link Scripture with religiosity as being unfair.

I would not have used torn pages from a Bible and would have probably found a different way of representing religiosity. But in doing so, the artist has merely destroyed his Bible, but it does not stop anyone else from accessing the Bible and its contents. The Word of God is not harmed by his actions. Because the Word of God as it is prayed and lived is actually meant to move from the pages of the book and enter into our lives and inform our actions. And is that not his point? Believers should not be hypocritical. They should not hide behind pious words and then act sinfully? If we only keep the Word of God on the pages of a book then we are not allowing it to transform our lives.

The Word of God as it is prayed and lived is actually meant to depart the pages of the book and enter our lives and inform our actions.

His artistic critique is against the hypocrisy of religion, but that can be countered with an experience of more authentic religion devoid of the capitalist and prosperity-cults he criticizes. Unfortunately, the malice and attacks that have characterised this outcry may have served to reinforce his perception of religious hypocrisy.

Accusations of satanism are a step too far

I also believe the charge of Satanism levelled against a young learner without any knowledge of his particular situation, to be rather unbecoming – in fact it is scarily reminiscent of the Witch Trials! Satanism is a serious charge in the Church, and one that should not be made lightly, and certainly not without evidence. One would be severely guilty of harming someone’s reputation otherwise. I think we can see in this case the effort of a person to reconcile his faith with the hypocrisy he knows deep-down to be unchristian.

The charge of satanism can relate to someone who actively worships the devil in place of the Creator, and is profaning the objects of the Christian religion in their act of worship. This artwork was not an act of worship – indeed, the artist professes that he has lost his belief. It is a sad monument to his rejection of God because of the hypocrisy of believers and the presence of the prosperity Gospel in his experience of religion.

Do I find some of his artwork distasteful? Yes, in parts. But I find the prosperity cults and hypocrisy in religion distasteful too. His artwork about a distasteful subject, is likely then to be distasteful in its object. But my faith is not threatened by it. Is the artist making a valid critique? I think so. I have not been able to engage the artist personally, but were I to do so, my questions to him would be more around his substantive criticism of religion, rather than the artwork. His art has raised questions. By focusing on the art are we in danger of avoiding those questions?

UPDATE: Wednesday, 13 May 2020. This article was edited to include the name of the artist concerned after he gave us permission to do so. He also allowed us to link to his website and to show the artwork under discussion.

This article is archived here from my work for the online publication, Spotlight.Africa which I wrote whilst working for the Jesuit Institute South Africa. Spotlight.Africa was a work of the Society of Jesus in South Africa from 2017-2021.

- This was originally published at: https://spotlight.africa/2019/10/25/grantleigh-artwork/