Introduction

“T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E.”, by sculptor and artist Guy Ferrer, is composed of nine bronze sculptures, each representing a letter of the word “tolerance” and depicting aspects of a religion, belief or spirituality. It is currently on display at St Stithians College and I went to visit it this past weekend. (Full disclosure: I’m an alumnus of the school). I thought I would share my impressions about this intriguing artwork.

The artwork is on loan to the school from the Everard Read Art Gallery in Johannesburg. Their website states that:

“Guy Ferrer is French, of Catalan descent by his father and Italian descent by his mother. He was born in 1955 in Algeria, and this work has been exhibited in France, Germany, Poland, the United Arab Emirates, and South Africa. Conceived in the aftermath of 9/11 and in reaction to contemporary humanist religious tensions, this artwork presents Guy Ferrer’s reconciliatory vision. It is a message of hope stating that the communal and shared spiritual quest, inherent in our humanity, should be a source of convergence. Key to an essential commitment for respect and peace in the world, tolerance exists thanks to an effort of reflection, openness to others and imagination.

It is a message of hope stating that the communal and shared spiritual quest, inherent in our humanity, should be a source of convergence.

This major sculpture received wide acclaim through its exhibitions in La Monnaie de Paris (January, 2008) and in the Jardins du Luxembourg, French Senate (summer, 2008). It has also been installed at the Goethe University in Frankfurt (Germany, 2009), the city of Poznan (Poland, 2009), the Palais des Rois de Majorque (2011) and the Campo Santo (2014) in Perpignan (France). Three of the eight editions of this work have been installed on a permanent basis at: the François Mitterrand’s park (Saint-Ouen, France); the forecourt of the Government Palace in Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates); and the district of Port Marianne in Montpellier (France).”

Mark Read, Director of the Everard Read Art Gallery, speaks about Guy Ferrer’s T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. and its relevance to South Africa and the world in 2020. // YouTube/St Stithians College

Mark Read, Director of the Everard Read Art Gallery, speaks about Guy Ferrer’s T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. and its relevance to South Africa and the world in 2020. // YouTube/St Stithians College

The artist believes that each installation of this artwork “serves as a landmark, a focal point for welcoming other artists, students and entire communities to join in spreading the fuller message of Tolerance, Compassion and Brotherhood”, which is the artist’s intention behind creating an artwork that is truly greater than the sum of its parts. The placing of the figures next to each other represents how each can be pursued without threat to the other and yet stand together as testament to the importance and relatedness of all.

I am aware that the observations below are seen primarily through a lens of my own faith and spirituality, and from what I have encountered and read about in other spiritualities and religions. I hope that members of other Faiths might also contemplate this artwork and offer insights that resonate with their own tradition. There is certainly no last word in appreciating this conceptual masterpiece, but I humbly share my impressions in the hope that it might stimulate or awaken your own.

My impressions of the ‘T’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Some people may immediately be drawn to the cruciform shape, and the branches that grow out of the figure’s head might remind one of a crown of thorns. But these thorns appear to have grown and appear more like living stems, and perhaps that is why the figure is not attached to the ‘crucifix’ but appears in front of it. There are some types of crosses, like the Franciscan Tau cross which has a T-shape too. I admit this could be something one can read in the artwork, but looking behind it there is no vertical beam, and so no cross, so whilst I think it’s tempting for Christians to read a cross into this and see Christ, and growth and new life where there was death, I see in it allusions to an earlier spirituality that is more naturalistic and elemental and sees the deity in nature, and how each of us are connected to creation, not just as a part, but as a potential source for the growth (or decline) of the natural world.

I see in it allusions to an earlier spirituality that is more naturalistic and elemental and sees the deity in nature, and how each of us are connected to creation.

For me, the outgrowths of branches from the head reflect a growing understanding of our mind and reflect an ability to comprehend the relationships and links in all of creation. For lack of a better word, the beams behind the figure’s head, remind me both of flight – the wings of a plane (or perhaps, in an abstract way, an angel?) – and so the element of air, the boughs of a tree, and so nature, or even something metallic, and the link to what is deep in the earth. This creates a vertical tension that goes from the depths to the heights and provides the necessary boundaries for considering the divine. If the beams are seen as roads or paths, the figure could be seen to stand in the crossroad which is always a locus of decision and spiritual encounter. The figure appears robed and its hands are joined in an act of contemplation. The growing outcrops represent creativity, and like antennas, a desire to sense the beckoning unknown.

My impressions of the ‘O’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

What strikes me here is that the focus is on the head, which is large, suggesting intellectualism and the importance of reason within religion. The focus here then is the tension between what one thinks and what one does, finding true authenticity in other words. The hands form a circle that pass through the mind which reminds me of the Buddhist notion of karma, the belief that one’s actions in the past and present impact one’s future. (A circle is also a common feature in traditional architecture, e.g. in Africa, the Tukul, representing the home or local culture.)

The thoughts in one’s head are translated into actions represented by one’s hands, and how habits of virtue or vice are formed through attention or inattention to what one contemplates. The cyclical nature also reminds me of the religious belief in reincarnation in some non-Christian traditions, and there is also a resonance with Ouroboros, the serpent swallowing its tail, signifying eternity in Gnostic imagery.

The eyes appear open but there is no mouth, and the actions enter the head through the ears. This reminds me of the ill-effects of gossip on others, and of St Ignatius’ observation that love shows itself more in deeds than in words.

The cyclical nature also reminds me of the religious belief in reincarnation in some non-Christian traditions, and Ouroboros, the serpent swallowing its tail, signifying eternity in Gnostic imagery.

On the other hand, the absence of a body, and the presence of hands can also allude to the need to listen and help those who cannot help themselves. There is an element of compassion here for those who are not fully aware or physically fit. Without being able to voice what one feels, one can only observe one’s actions, and yet recognise how there is much going on in the mind that one can never be aware of, and so compassion to all is what is important.

There is also the allusion to a halo, a traditional artistic depiction of holiness, which was borrowed in a way from the ancient Egyptian religion sun or nimbus. The gnarled image created by the hands is also reminiscent of antlers which is also suggestive. In English folklore, Herne the Hunter is adorned with an antler like headdress in imitation of the Celtic pagan religion image of the antlered god Cernunnos.

The hands that are held together in a circle may also be reminiscent of the Celtic hand-fasting traditions that in other cultures takes the form of a marriage, or bonding ceremony. In Jewish tradition, during the wedding ceremony, one or both members of the couple walk or dance in a circular way in what is known as the hakafot. In recalling matrimony one also remembers the values of loyalty, friendship, covenant and relationship, all of which God shares and constantly renews with us, as we share them with each other in marriage.

My impressions of the ‘L’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

This bronze figure is sculpted to depict the texture of wood, again suggesting a spirituality that is in tune with nature and the world. The rootedness of this image speaks to how one must always ground oneself in experience and reality. The sexless figure speaks to me of how gender is not a barrier to communication with God.

The central feature in this image is the face that appears askance, as you can see from the inset image, recalling the need for humility to ponder the divine, to be awakened not by answers, but by questions that divinity poses to humanity and – in this case – the whole created world.

One ear is enlarged, depicting the emphasis on listening in all contemplative spiritualities. From an African perspective, the ear is a totem of leadership that is best practiced in patient gathering and meeting to listen, e.g. baraza, insaka, indaba. The protruding eyes suggest the art of truly seeing.

The hands hold nothing, again suggesting the act of listening and seeing without distraction. The ear to God and the eyes confronting the onlooker speaks of Prophecy, another important part of religion.

The hands hold nothing, again suggesting the act of listening and seeing without distraction.

The figure is upright, representing all that is moral, good and upstanding. It is not bent or burdened by sin or moral compromise. There is no wagging finger or violently resistant upraised hand, but rather just the askance glance that questions, persistently, the status quo and queries the place of justice and moral uprightness in our current situation.

My impressions of the ‘E’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

The golden crescent moon reminds me initially, and maybe naïvely, of Islam, but also of all the religions that ponder the awesomeness of creation, or contemplate the movements of the stars and planets. Furthermore, how one can find God in nature by observing the majesty and vastness of space, while simultaneously honouring patient attention of reason, of science, and the laws of nature, in their interpretation of the origins of our universe.

The figure is seated in a contemplative pose, looking forwards. From an African perspective, it is a wisdom figure in its pose and facial expression. The mouth is open as if in awe as the figure contemplates wonder.

The crescent has represented Byzantium, the Ottoman Empire, and by extension more popularly now Islam – though this is not universally accepted by Muslims. As a representation of the regular movement of the solar system, it also represents time, and our understanding of how we are created in time and space, and the relative minuteness of our space in the universe. Yet we are gifted to be able to be aware of all this and contemplate it, and so be amazed and in awe of the Creator who created us.

Prayer in spiritual traditions often privileges silence and separation, times of concentrated listening and seeing.

This statue also evokes the notion of a teleology – a plan and purpose – that prompts us to contemplate the ends for which we were created in the first place. The mid-position in which the figure is situated also speaks to how one needs to be removed from the mundane pursuits to become aware of these great truths. One needs to separate oneself from the World, to create time and space for contemplation to recognise and understand the significance of what one becomes aware of. This is why prayer in spiritual traditions often privileges silence and separation, times of concentrated listening and seeing to shut out the distractions and become truly conscious, truly free, truly aware, and so in awe, and in gratitude for one’s blessings in being created.

My impressions of the ‘R’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Whilst some might see in this face the image of a wizened crone, playing on the theme of Wisdom or Sophia, which in one understanding is the one who is skilled with techniques and tools (which could be what she is holding), I believe that this figure represents more of the pilgrim, and all the spiritualities that see faith as a journey. The figure is looking backward, reflecting on its past, but the staff and movement is forward, thus denoting movement and a desire to transcend the present.

Adherents of spiritualities that recognise that life is a journey are not paralysed by sin, nor forgetful of their past even as they glory in the future. The craned neck represents effort and the covered head and cloaked figure evoke an image of a seer – that is to say, a person who sees clearly.

The forward-step cannot begin without first looking back.

Without reflecting on one’s experience one never learns and many religious traditions stress the importance of being able to learn from one’s mistakes in order to move forward. The forward-step cannot begin without first looking back, reflecting on one’s experience and learning.

It is also possible to think of the figure as the travelling traditional healer or itinerant medicine man/woman. From an African perspective this would allude to the practice of divination.

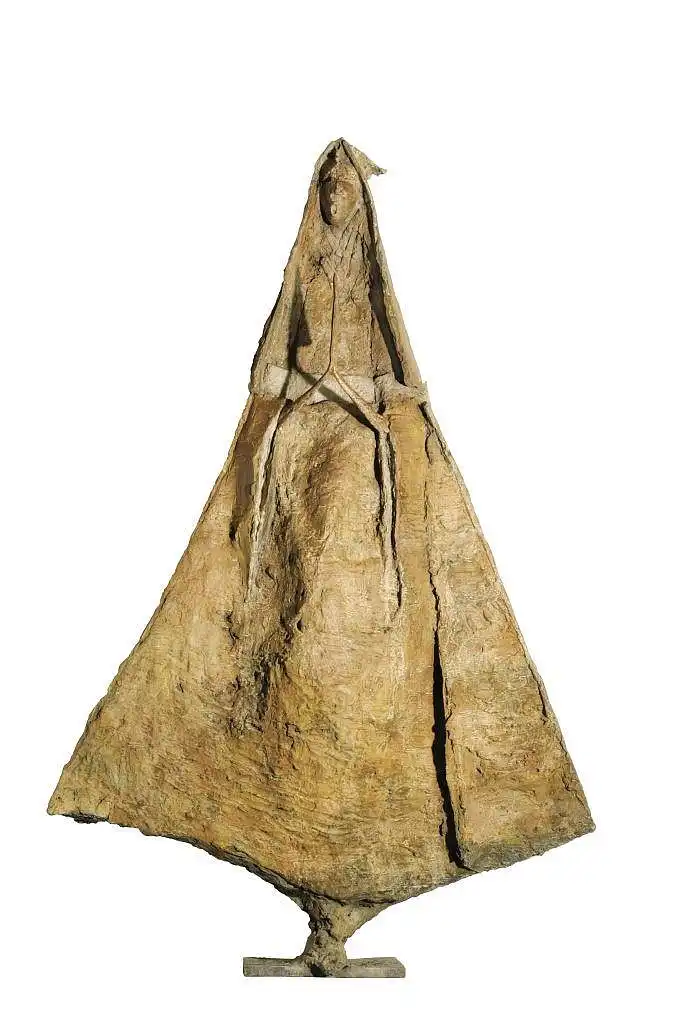

My impressions of the ‘A’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

For me this is the most Christian image. The artist speaks of how each of these letters represent emissaries of religions and spirituality, and for me this is a classic depiction of the Virgin Mary, who was the emissary or envoy who bore Christ into the World, and is considered to be the Mother of God.

As mother, it is also representative of all the spiritualities that celebrate or honour the feminine. From an African perspective motherhood, and fertility, are highly treasured. Her joined hands in the symbol of prayer, and what appears to be a sign of pregnancy, symbolise the willingness to accept life and bear it in a prayerfully accepting stance of co-creation with God, participation with God’s will, and models how we should all allow God to work through us. The hands, viewed from the side, appear to be similar in shape to a trowel used to plant and plough – again a reference to fertility, and how one can allow oneself to a be a tool to be used for God’s greater glory.

The habit that she wears, a sort of dress also speaks of the religious values of modesty. Her mouth is open, recalling the Magnificat of praise in recognizing the wonders that God has wrought.

The shape of an arrow also alludes to an upward motion. This recalls for me the canticle Mary prays recorded in Luke’s Gospel in which the Lord will lift up the down-trodden and pull the mighty from their thrones, and how he has raised Mary to this special honour of being the Mother of God, whilst at all times honouring the free will of each human person.

My impressions of the ‘N’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

These figures remind me of the Yin and Yang of eastern philosophies and other dualist traditions. The interlinked arms reflect the intrinsic relationship between the progressing and declining figures that simultaneously pull-up and pull-down. There is thus a constant tension in this image between the figure that is moving forward and pulling upward, and the one that is falling and pulling downwards (reminiscent perhaps of ‘spiritual warfare’)… The head of the figure standing and pulling is a skull, which seems to be a depiction of death to which we are all destined. But this journeying towards death becomes the support for new life, thus reminding us of reincarnation, and from an African perspective the connection of the living with the dead, e.g. Ancestors. This is also present in other spiritualities, e.g. the communion of Saints, who continue to live in the heavenly realm.

The question of perspective is also raised here and how one’s past is part of our ability to move forward. The figures appear unclothed, suggesting that our nakedness and vulnerability reveals our connections to each other and to our past.

There is thus a constant tension in this image between the figure that is moving forward and pulling upward, and the one that is falling and pulling downwards (reminiscent perhaps of ‘spiritual warfare’).

There is also an element of balance in this image and many spiritualities help one to become more balanced. The strength and visible muscles on the figurines also reflect how religion demands stamina and how bodies are seen to be a temple of God. The falling figure also supports the advancing one and this is reminiscent of how one’s faults might be the occasion for inspiring others and that true spiritual leaders are not perfect but rather conscious of their own wounds and defects, for perfection exists only in God.

This is also one of the sculptures with more than one figure, revealing how one is joined together to one’s life partner and how triumphs or defeats, successes or failures, can lift one up or pull one down, but the journey forward is made possible together. Unlike the community emphasized in the ascent of prayer to God in the final letter E, this shows how the coupling of two humans can be an aid, or a burden in living well.

It might also represent the two sides in each of us, the public and private self, the side we show to the world, and the hidden self we’re ashamed of, and yet by joining them together, we show what God sees – the total whole. The theme of compassionately uplifting the other, or oneself, is also reminiscent in these two figures. There’s the flexibility within the image that might speak of the need to have an open mind within Spirituality, to see beyond horizons and thus be open to a God of Surprises.

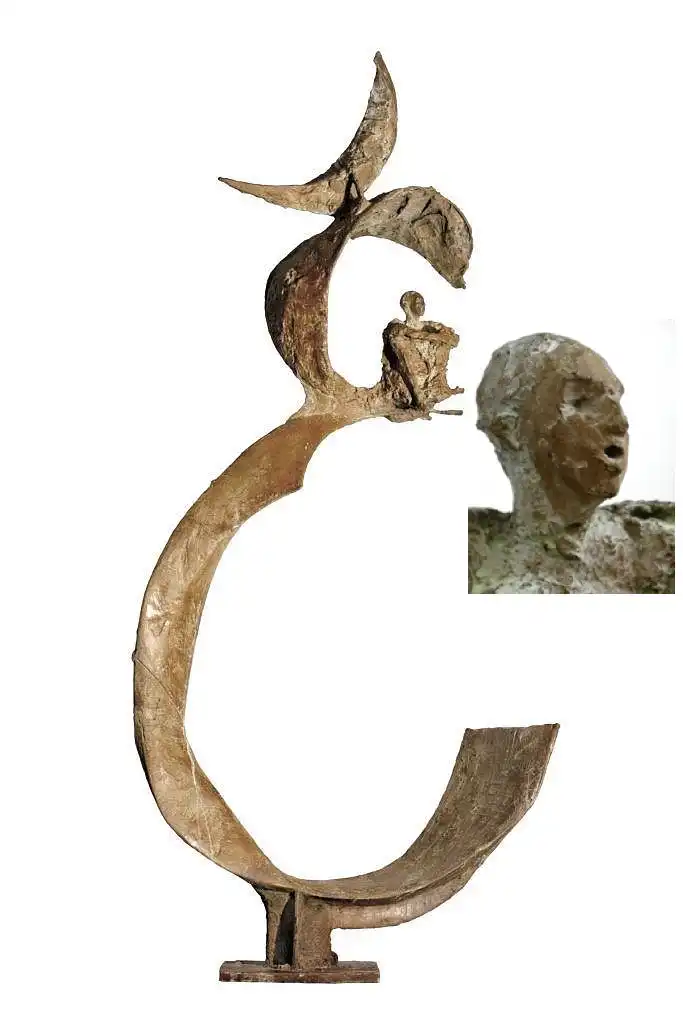

My impressions of the ‘C’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

There is a serpent-like sea creature that is curved in on itself, much like we are when we give into temptation and fall into sin. The tail contains a dangerous looking claw, or perhaps it is a scorpion’s tail – the sting of death – which represents the total self-injuring nature of sin.

This represents for me how an inward looking, self-centred understanding of religion can lead to death, as represented by the skull that appears to have been swallowed by the serpent. The fins and the sea creature again point to nature, but in certain faiths the recognition of God in creatures might also be represented here.

The fins also have a shell-like quality, representing the symbol of pilgrimage. The inward curvature of this image and cyclical nature of oneself also reminds one of the deathly nature of embarking on a spiritual journey with oneself as the centre. True religion, to be life-giving, must be other-centred, drawing oneself outwards into relationship, and not selfishly contemplating oneself. A drowning connotation of being at sea and chasing one’s tail whilst forgetting to stop and breathe also comes to mind, which creates allusions to the false satisfaction in needless consumption and consumerism.

True religion, to be life-giving, must be other-centred, drawing oneself outwards into relationship, and not selfishly contemplating oneself.

The interrupted curve, might also allude to the break in eternity which the O figure’s nimbus or circular sign spoke of. This break might represent the experience of sin which interrupts the building of the Kingdom of God on earth that Christians are called to work towards, “as it is in Heaven”, according to God’s will.

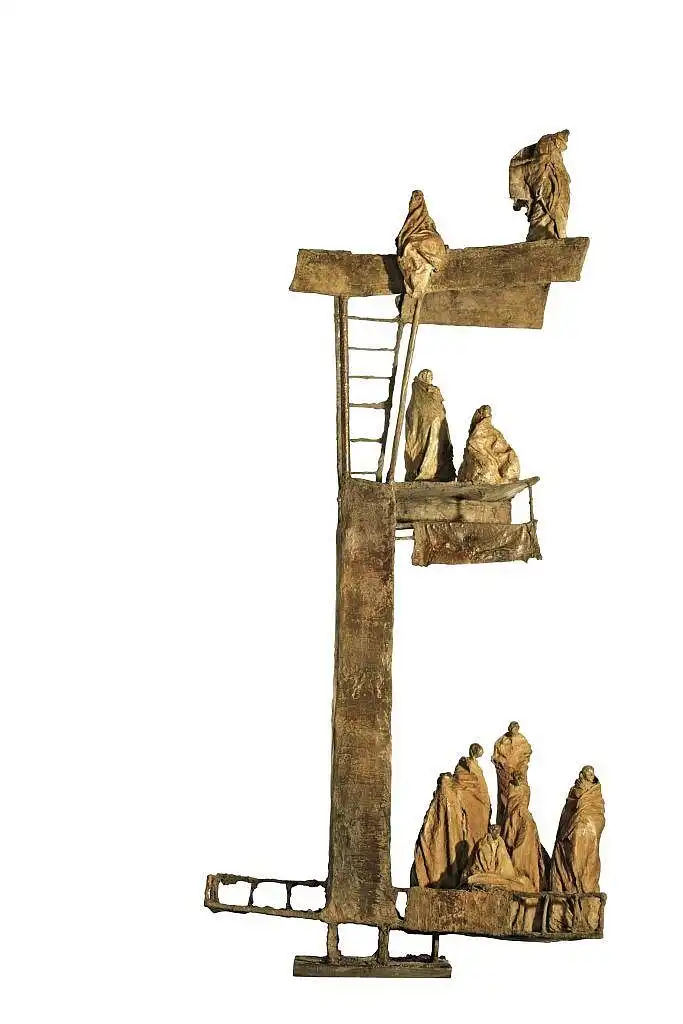

My impressions of the ‘E’ artwork.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

Guy Ferrer, T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. Bronze.

This is my favourite piece. It makes me think of the contemplative tradition within community that is common in many religions, as represented by what seems to be a community of Tibetan monks. As community, it also invokes the African concept of Ubuntu and the vital connection that is present. The figures evoke a movement together with one another but also a separation as they ascend.

The sculpture shows figurines on three distinct levels, recalling perhaps Dante’s Divine Comedy which tells of the journey from Hell through Purgatory to Heaven. (Similar ‘realms’ of existence are common in mythology, for example in Norse Mythology, Asgard and Midgard are joined together by the Bifröst, a rainbow bridge, whose colours are in a ladder-like formation). One can also conceive the levels not just as realms, but as stages in a spiritual journey.

At the bottom, the community of monks are gathered around a seated guru or master as they become disciples in prayer. They are focused on their lives and are situated on a spacious platform that is balanced on both sides (a horizontal ladder, which reminds us of the Ladder mysticism in certain Eastern and Western Christian spiritualities). To ascend they have to use the ladder, harnessing and transforming their surroundings, to reach the next level – a metaphor of prayer, and how one can ascend and descend and that the journey takes place with deliberate steps forward and backward, up and down.

The middle section shows a couple of monks on a limb with one climbing to reach the height where the lone figure is. The ‘out on a limb’ notion represents the faith that one must leave the safety and security of certainty and allow oneself to risk belief. The figure on the top near the edge is windswept and to me is listening to that silent whisper of God away from the others in silence and solitude, as the figure looks outward towards the unseen, but ever-expanding horizon of their awareness.

It makes me think of the contemplative tradition within community that is common in many religions, as represented by what seems to be a community of Tibetan monks.

The top represents the mountain and mouth of the cave, which is an allusion to Plato’s allegory of the cave, the movement from ignorance to spiritual enlightenment. This is also an allegory of prayer and the contemplative tradition, a part of religion and spirituality that appreciates the mystical and self-revelation of God to each of us. The community aspect here, where one can be held to account in one’s spiritual ascent or descent, comes after the considerations of a couple and selfishness and perhaps ends with the assurance that with the support of true community it is easier to find God.

Whereas the first ‘E’ appears in cursive script, and is reminiscent of a pre-existent sign or relationship – like a mathematical symbol or law of nature (in which we can only marvel) – this final ‘E’ has the look of a construction site, alluding to how one must work and build a spiritual relationship with God. So if the pre-existing relationship shown in the first ‘E’ might represent the foundational and unchanging spiritual orientation that God enjoys with each part of God’s creation; then the operative and immediate spiritual orientations that we must continuously construct or reorient ourselves Godwards is represented in the second ‘E’, especially through the motifs of ladders and scaffolding, which reflect the temporary and fleeting nature of our existence as we strive to commune with the eternal Divine, constructing a relationship we hope can glimpse at divinity. In the striving this loving relationship is developed, experienced and extended allowing our image of God, of ourselves, our neighbours and our world to be purified into harmonious right relationship.

The artist, Guy Ferrer, speaking at the International Festival of Faiths about T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. // YouTube/Festival of Faiths

The artist, Guy Ferrer, speaking at the International Festival of Faiths about T.O.L.E.R.A.N.C.E. // YouTube/Festival of Faiths

Conclusion

Whilst individually there is much to appreciate in the individual statues, there is still yet much more to appreciate in the artwork as a whole. In standing side-by-side the individual sculptures point to how faiths can coexist, in support of one another’s shared search and worship of the Divine in our natural world. Seen together, each part illuminates aspects in the other, thus offering a richer and even more prayerful encounter.

When I viewed this artwork with a friend, I made the remark that in my view, tolerance is a fairly low bar to expect from people. Tolerance does not demand as much as what is really required in our world, which I believe in our current time and context is rather fraternity, a stronger value which embraces ‘One and All’ (the school’s motto) more completely. Rather than just being tolerant of another, fraternity demands that we see each other in relationship; that we be “our brother’s and sister’s keeper”; and that we see ourselves and our relationship to each other as impactful, with duties and responsibilities not only to God, but to each other, and to our world.

Rather than just being tolerant of another, fraternity demands that we see each other in relationship.

This important artwork, however, emphasizes what is still necessary, and though I feel it is not wholly sufficient to the true task at hand, it does lay the foundation for a future building of fraternity – where, in the Christian sense, we acknowledge and affirm, every person as being created in the image of God.

Reflecting on the different traditions, I also see, throughout history, how there has been a progressive movement from animism to polytheism to monotheism, and how, from my tradition’s perspective, Christians might recognize how the Triune God has gently sensitized humanity throughout history to God’s true nature, which as Christians we understand to be Trinitarian. In recalling tolerance for these different religions, or more accurately, for different apprehensions of the Divine by other human beings, one can see in that act a recognition of God’s patience with us throughout history as we come to understand God more deeply, and how God is willing to reveal Godself to each person where they are, to the limit of their understanding and awareness.

As Christians, we believe in a Trinitarian God. Theologians would teach us that the Trinitarian reality is divine community, a multiplicity in singularity, pure relationship. We believe that in the Triune God one finds diversity without subordination, in the one Godhead we find distinction without separation or division. We believe that the Trinity is a model for human societies as well, showing us how we must relate in love without fear, competition or distorted power relations. In this sense, reflecting on the greater history of divine revelation, one can see the patient respect of God to each of us in our particular moment in our development and individual context. We should not therefore be threatened by other’s views of God, as the God we believe in desires only to reveal Godself, and has revealed Godself in ways that lead others to understanding various aspects that this artwork shows can be held both in common and in creative tension.

When we as Christians advocate for justice, we do so not because we are politically-correct but because if each of us are created in the image of God – and we take that seriously – then our differences can never be a cause for division or fear. Our differences should be something that are celebrated, and – I have to say – not merely tolerated, as they reveal parts of God hidden to each of us. Nonetheless, this artwork is important for highlighting aspects of God that might have remained hidden to us. As Church, we must move beyond rhetoric, and create the policies that reflect a real honouring, prizing and cherishing of the diversity of the human family. Part of that diversity is in how we approach other religions and our understanding of God. In Nostra Aetate, the Second Vatican Council authoritatively taught that:

The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these religions. She regards with sincere reverence those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings, which though different in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of truth which enlightens all men.

Nostra Aetate, Paragraph 2b.[1]

It is the same God, we believe, who is the source of truth that enlightens humanity, and, if we realise the progression mentioned above, then different people are at different stages of understanding and relating to God. Tolerance is a necessary first step – but I hope it is not the last one.

In an age where religious ignorance and intolerance fuels fear and suspicion, and ultimately terror and wars, it is vital that religious tolerance, and religious freedom, be actively promoted. These are values guaranteed in our Constitution, but like all values, they need to be personally appropriated before they can be communally celebrated. I hope that visitors to this artwork might deepen their understanding in their encounter with Guy Ferrer’s emissaries, and allow themselves to be converted into emissaries of peace, fraternity and tolerance themselves.

Guy Ferrer’s artwork is worthy of humble and patient attention since from every angle and in each encounter, there is something that speaks of God’s desire to reveal Godself… if we but only have eyes to see.

This article is archived here from my work for the online publication, Spotlight.Africa which I wrote whilst working for the Jesuit Institute South Africa. Spotlight.Africa was a work of the Society of Jesus in South Africa from 2017-2021.

This was originally published at: https://spotlight.africa/2020/09/16/thoughts-on-guy-ferrers-t-o-l-e-r-a-n-c-e/